The Mountain Goat can be distinguished from all other ungulates in British Columbia by its characteristic all-white or light-cream-coloured coat, pointed ears, short beard and short black pointed horns. The only other all-white ungulate is the Dall’s Sheep, but its fur is much shorter in winter and its legs are slender and lack hair chaps. The horns of adult male Dall’s Sheep are much more massive than those of Mountain Goats. The horns of female and yearling male Dall’s Sheep are similar in size to those of Mountain Goats, but they are brown, ridged and blunt tipped, not black and pointed.

Some people still confuse Mountain Goats with female Bighorn Sheep where their ranges overlap, despite the different colour and the different horn and body forms. Bighorn Sheep have a brown coat, large white rump patch and a short black tail, in contrast, to the all-white Mountain Goat; and the horns of female Bighorn Sheep are brown and blunt-tipped in contrast to the thin, sharply pointed black horns of the Mountain Goat.

Mountain Goat skulls are distinguished from the most similar species (e.g., female and yearling male wild sheep) by the presence of sharp, black horns, the short, straight, sharp-pointed horn cores that, like the horns, are round in cross-section, and the much narrower cranium and orbital region. Like those of female and young male wild sheep, Mountain Goat skulls are quite fragile. The metapodials are characteristically short and robust, compared to those of wild sheep or Odocoilid deer of similar size. The soft pad of the Mountain Goat’s hoof is also unique among B.C.’s ungulates. Signs of Mountain Goats along trails are clumps of white hair they have left behind when shedding their winter coats.

Tracks of Mountain Goat are similar in size to those of Bighorn Sheep, Thinhorn Sheep, White-tailed Deer and Mule Deer. But the impressions of Goat hooves are more rounded at the tip than those of deer, and the individual hoof tracks tend to be narrower with more parallel sides than those of wild sheep. Distinguishing faecal pellets of Goats from wild sheep and even deer, is difficult.

|

After a gestation period of 147 to 178 days, young Goats are born in late May and early June. A female usually isolates herself in rugged terrain to give birth. Normally one offspring is born, but twins are not uncommon and triplets occur rarely. Shortly after birth, young Goats follow their mothers, who are highly protective of them. Mothers and young may form small nursery groups in spring, and even larger temporary aggregations in summer. Young Mountain Goats weigh between 2 and 3 kg at birth and are all white, like adults, although some young may have a brownish dorsal stripe from the neck to the tail that disappears before it is a year old. By the end of their first autumn, young have usually developed short black horns, 25 to 65 mm long, just slightly longer than the hair on their heads. The young Goats grow rapidly, but most yearlings are smaller than adults, and they have a concave facial profile. Typically, two year olds can also be distinguished from adults by their smaller bodies and horns, but not in populations living in good conditions. The horns of a yearling in spring and early summer are usually shorter than its ears, but by autumn the horns are as long as the ears; those of two year olds exceed ear length. Goats are usually sexually mature at 24 to 30 months of age. Most females probably bear their first young in their third year; males do not fully participate in the rut until they are at least five or six years old.

|

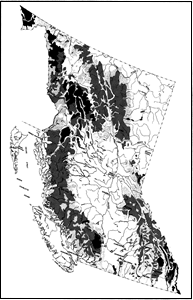

Mountain Goats are able to live on a wide variety of plant foods – grasses, forbs and much browse. The Mountain Goat’s wide food habits together with an ability to tolerate deep snow for short periods probably account for its widespread distribution throughout the province. For example, in the Coast Mountains, sudden heavy snowfalls can trap Goats for several days in shallow snow wells at the bases of mature conifer trees. The Mountain Goat’s ability to subsist on any available plant material means the difference between life and death.

|

Unlike most other ungulates in the province, Mountain Goats show limited external sexual dimorphism. Horn shape is probably the best way to distinguish adult males from females at a distance; when viewing the animals close-up or examining a skull, the basal diameter of the horn is a more reliable indicator. Most adult female horns show a distinct change in curvature near the tip, whereas the curve of the male’s horns is smooth. Any animal seen to squat while urinating is almost certainly a female, and in short summer coat, a male’s scrotum is visible.

In spring, Mountain Goats can appear to be in poor condition, because large patches of their long coat are missing or hanging loose. This is normal and is simply a sign that they are shedding their heavy winter coats. Like many other species, pregnant and lactating females usually lose their winter coats later than other age-sex classes.

Mountain Goat age can be estimated by counting horn sheath rings (annuli). For animals older than about six years, this becomes difficult because successive rings are crowded together, especially in females. Also, the first ring, developed in the animal’s first winter, is usually no more than a smooth ridge that can be difficult to distinguish. The second year’s annulus is often the first easily recognizable ring. The emergence of permanent teeth and the replacement sequence of the deciduous teeth, can also be used to estimate age up to three years of age, and for older individuals, cementum annuli counts provide a reliable estimate.

Mountain Goats typically live around 10 or 11 years, with the oldest reported specimens being a 14-year-old male and an 18-year-old female.

|

Not much is known about causes of mortality. Diseases (e.g., contagious ecthyma, white muscle disease) and parasites (e.g., wood ticks, lungworm) have been documented. The main predators of Mountain Goats are Cougars and Wolves; occasional predators are the Bobcat, Coyote, Wolverine, Grizzly Bear and Black Bear. Like wild sheep, steep cliffs provide Mountain Goats with essential security against mammalian predators, although the cliff habitat may be less useful against Golden Eagles which sometimes prey on young Mountain Goats. Eagles have been known to knock juveniles off cliffs, then swoop down to feed on them. Harsh winters also increase Mountain Goat mortality, and are especially hard on young animals, while avalanches sometimes take a toll on all ages. When being captured and handled for transplants or research, Mountain Goats can suffer from capture myopathy (often mistakenly called White Muscle Disease, which is a disease of Cattle and Domestic Sheep). As a result of stress induced during capture efforts, Mountain Goats may sustain muscle damage. In extreme cases, this can cause death at the time of capture, or afterwards because the animal is more susceptible to predation. In B.C., selenium is a mineral often in short supply, and low selenium levels in a Goat’s body may predispose it to capture myopathy.

|

Mountain Goats, primarily females and young, live in small groups of usually two to ten members, but sometimes in summer, larger groups are seen. Most often, the larger groups form in alpine meadows when feeding conditions are good. In some areas in B.C., more than 100 animals have been counted in these mother-young aggregations in summer. Outside the mating season, adult male Goats usually live alone or occasionally in the company of two or three other males.

Both sexes of Goats are aggressive by nature and their sharp, smooth horns are dangerous weapons. If fights occur during competition, both males and females can inflict serious wounds, and even lethal injuries on rare occasions. Mountain Goats seem to avoid fighting unless they have to. Instead, males use various threat and lateral dominance displays that may draw attention to their horns or body size. Their characteristic shoulder hump probably helps increase the visual effectiveness of the lateral display. When displaying laterally, a male will lower his head, tuck his chin between his forelegs, and with arched back, walk in a stiff gait, circling and pointing his horns at his opponent. This behaviour may encourage one of the males to leave, but if not, one or both may make upward, stabbing blows with its horns, usually at the opponent’s rear flank. The skin along the sides of the rump seems to be thicker, and may provide some protection against horn blows. Their characteristic aggressiveness and dangerous weapons, along with their preference for steep cliffs, may explain why their average group sizes are smaller than other mountain dwellers such as Bighorn or Thinhorn sheep. Besides a bleating sound audible at close quarters, both males and females make a variety of vocalizations, most often during aggressive encounters.

The social behaviour of Mountain Goats is poorly understood and our limited knowledge is based on a few studies. The timing of the mating season in British Columbia varies, depending partly on latitude; in some areas, mating begins in late October, but more often, it starts in early November and continues until mid December. During the rut, males rub their horn glands on bushes, and while it probably has some signal value, the function of this behaviour is unknown. During the rut, a male will also paw a depression in the ground, urinate in it, then rub his rear flanks in the wet dirt. Presumably, by covering himself with urine he increases his odour and so advertises his condition to females and rival males. In areas with dark soils, wallowing males develop dark patches along the flanks. Mountain Goats also wallow in summer; they do not urinate in the pits but roll in them for dust baths. They perform similar behaviour in snow patches in summer, possibly to reduce insect harassment or to stay cool.

A courting male will approach a female in a crouch, neck extended and nose pointed slightly upward, tongue flicking in and out. This is an extreme form of the more usual mating approach used by courting males of most other B.C. ungulates. The Mountain Goat male, however, must be especially careful when approaching an adult female, because she is all too ready to threaten him with her sharp horns. Once close to the female, he will nose her rear and flank, and gently kick her with a front leg. If she urinates, the male sniffs her and performs a lip-curl to test her reproductive condition. When the female is in full heat, she stands and allows the male to mount her, and she may even mount the courting male. Females are thought to remain in oestrus for 48 to 72 hours.

|

|